In this study we used the system dynamics to formulate

research in land-use planning by modeling the dynamics of “informalization”

in land-use controls. We found that our approach had several

advantages compared to traditional social science investigations.

Using SD, we combined distinctly different theories to build

a consistent model of land-use review processes. Furthermore,

we were able to maintain the richness and complexity of our initial

conceptualization by combining quantitative and qualitative approaches

and the model provided an anchor for the subsequent stages of

analysis and interpretation. Here we describe this model.

The formal mechanisms of design review in its broader sense include the establishment and implementation of traditional planning controls. Here we will first introduce the concepts of formal and informal controls and then discuss traditional land-use and design controls in terms of their main assumptions. Then we explore their contradictions with the concept of sustainability; the idea of rule-governed spatial morphology and its compatibility with the desire for place-making; and the issues of use and abuse of discretion and implications for participation.

a. Formal and informal forms of control

Governmental control over social activities can

be informal as well as formal. Formal control assumes a bureaucratic

process working efficiently by means of written law, intended

to be a “gapless,” internally consistent, abstract,

and rationally designed system. The application of law to any

specific case is politically neutral and predictable because the

decisions are logical deductions from the law. This process is

administered by specialized professionals acting as neutral bureaucrats.

Max Weber (1954), who says that formal control is the ultimate

state in the evolution of law, describes how the internal logic

of this ideal type works:

First, that every formal legal decision be the ‘application’

of an abstract legal proposition to a concrete Ôfact situationÕ;

second, that it must be possible in every concrete case to derive

the decision from abstract legal propositions by means of legal

logic; third, that the law must actually or virtually constitute

a ÔgaplessÕ system of legal propositions, or must,

at least, be treated as if it were such a gapless system; fourth,

that whatever that cannot be construed legally in rational terms

is also legally irrelevant; and fifth, that every social action

of human beings must always be visualized as either an ‘application’

or ‘execution’ of legal propositions, or an infringement

thereof (Weber 1954, p. 64).

In the field of sociology of law, informal control is defined by legal empiricists (also known as legal realists) as the "living law," i.e., it is based on what is actually happening in society. For example, Macauley (1966) analyzes how formal legal activities create and support informal processes. He shows how the introduction of new legislation sometimes confers on certain agencies discretionary powers or legitimacy to conduct mediation/arbitration between stakeholders. Shapiro (1981) shows that many informal processes occur in tandem with the formal activities of courts and suggests that judges play significant roles in initiating various informal processes such as mediation, arbitration, or negotiation. Likewise, Schuck (1986) describes the importance of informal processes in Agent Orange litigation. Drawing a picture quite different from WeberÕs, these scholars conclude that most of the time legal processes work not in isolation, but in conjunction with informal processes, where staff members act as participants rather than neutral bureaucrats, and political (or otherwise value-laden) interests exert influences on the process.

It is important to note that Weber (1954) sees the formal model as an “ideal type” toward which the legal processes in capitalist, industrial society move. Consequently, this model provides the comparative yardstick by which to judge existing legal processes. The legal empiricists, on the other hand, use the informal model to study the actual legal process and its social consequences. In this study we take these two types as the two extremes of a continuum (model presented in Figure 1), and expressing, respectively, modern and postmodern assumptions.

As any control system starts to employ discretion

and interpretation, its emphasis shifts towards procedural rules

and its substantive content begins to change. Formal rules contain

mandatory specifications leaving no need for mutual adjustment

through communication. They are abstract and general as opposed

to being situational or case-driven. Informal control systems,

on the other hand, operate with rules that are open ended assertions,

so that interpretation becomes necessary in applying the rules

to specific cases. Often (especially in common law) the rules

evolve case by case. Informal controls involve considerable communication

and negotiation.

Examples of formalization: territorial specialization and bureaucracies

For Weber, instrumental rationality, formal law, and bureaucracy are inseparable processes associated with the development of capitalism in modern societies (Bierne 1982; Giddens 1971). Weber (1991) argues that a new type of rationality, guiding an unprecedented kind of systematization of activities, emerged with the development of Calvinism and the spread of the Protestant ethic, and that this type of rationality constitutes the essence of capitalist development. Weber (1978) calls this type of rationality "instrumental rationality" as distinguished from "value rationality." Value rational action is "determined by a conscious belief in the value for its own sake of some ethical, aesthetic, religious, or other form of behavior, independently of its prospects of success" (pp. 24-25). Action is instrumentally rational when "the end, the means, and the secondary results are all rationally taken into account and weighed" (p.26). If "rationalization" is done to achieve, for example, equity as a value "consciously" held "for its own sake," then it is called "value rationality." On the other hand, if the purpose of equity is compared with some other (ethical, and/or aesthetic and/or religious) purposes to decide the most "productive purpose," then this weighing is called "instrumental rationality." For capitalist societies, it is fair to claim that instrumental rationality is synonymous with productivity-oriented rationality. What is important here is that when this kind of rationality is employed in planning it demands a high degree of technocracy and formal control.

Sack (1986) describes this rationalization and systematization process in terms of its territorial consequences. He defines the concept of territoriality as "the attempt by an individual or group to affect, influence, or control people, phenomena, and relationships, by delimiting and asserting control over a geographic area (p.19)". He suggests that one of the important territorial consequences of modernity is the process of "thinning out": making more and more places containers of just one type of activity. Sack argues that this process runs parallel with an increasing division of labor and increasing organizational hierarchies and specialization. For example, in a governmental office the hierarchy of the titles and roles assigned to the staff usually corresponds with the hierarchy of spaces that are assigned to house certain activities only (Lang 1987). Controlling activities in a hierarchical way by separating territories for different kinds of activities helps to rationalize and to systematize activities. The hierarchical classification of spaces and a control system that assigns restrictions over territories become necessary conditions for bureaucracies to function efficiently. Sack (1986) also argues that applying control to territories, rather than activities or actors, impersonalizes social relations. And impersonalization in turn tends to eliminate activities that are not related to the production process.

Territorial controls that are exercised by governments to impersonalize relations and to systematize activities imply high formalization. The use of territorial bureaucracies by the government to distribute public services and to collect revenues, an example of a modern bureaucratic system, is a sign of increasing formalism, a result of production-oriented rationality. The emergence of zoning can be seen as a part of this formalization and "thinning out" process.

Giddens (1991, pp. 16-17) argues that the primary characteristics of modernity are "the separation of time and space and their recombination in forms which permit the precise time-space 'zoning' of social life; the disembedding of social systems (a phenomenon which connects closely with the factors involved in time-space separation)..." The modern concept of land ownership -- usually referred to by planners as a "bundle of rights" --is an example of the disembedding of social systems. Land ownership is an abstract concept that defines the land as an empty territory that may in the future contain certain predetermined (and therefore controlled) activities. The concept of land ownership is crucial to administering formal, rational, territorial controls. It has been a guiding force behind the "thinning out" process and the formalization of land-use controls in the course of capitalist development.

Instrumental rationality and bureaucratization,

together with the idea of scientific management of human affairs,

provided the theoretical basis for modernist planning models,

which in turn established the procedural framework that supported

the "thinning out" process.

Modernist Planning

Friedmann (1987) summarizes the recent history of planning as a progression towards rationalization. Planning is a product of modern capitalist societies, and has progressed concurrently with the "gradual breakdown of the 'organic' order of feudal society" (p.21). Thus, one of the consequences of the broader changes in social structure was the emergence of planning as a distinct social function. In the post-WWII era many contemporary planners advanced a theory of planning based on instrumental rationality. During the 1950s and 1960s, Western planning thought became almost coterminous with the rational-comprehensive model (Weaver et al 1985, p. 157) that provided an abstract and idealized linear procedure efficiently linking available means to given ends. For example, Taylor (1984) invites scholars to advocate and apply a procedural planning theory that involves identifying the problem, identifying possible courses of action, evaluating these possible courses, implementing them, monitoring, review, and evaluation. The theory implies a linear step-by-step process abstracted and freed from the specific context of particular situations.

Inherent in instrumental rationality is also the

notion of planning as a means to apply "objective knowledge"

to public decision making. For example, Faludi (1985) states

that in the same manner that the scientific method provides methodological

standards for scientists, instrumental rationality provides standards

for planners to demarcate "responsible” decisions from

"ill-founded" ones. According to Faludi, instrumental

rationality is not only a tool to achieve the best decision, but

also a condition of legitimation. In other words, Faludi believes

that "objective knowledge" together with formal procedural

standards of rationality, gives planners grounds to claim that

their decisions are value-neutral and universally valid. The

efficiency of territorial bureaucracies and instrumental rationality

may explain the emergence of zoning in the U. S. But the same

framework is inadequate to explain its historical development.

A case of informalization: a short story of zoning in the U. S.

As it emerged in the 1920s, Euclidean zoning was intended to be a simple and rational land-use control system, similar to the formal ideal type. As Babcock (1966, p. 4) states, "zoning was no more than a rational and comprehensive extension of public nuisance law." It was a regulatory system to prevent "pigs in the parlor," as the U. S. Supreme Court stated in Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co. (1926), a landmark case in which the zoning authority of local governments was recognized as a valid use of police power. It was a rationally designed abstract system and therefore could be adopted easily by many other communities with only some small changes. As Babcock (1966) states, "it was a simple matter to draw lines on the municipal street map showing the boundaries of the districts: six pages took care of the simple requirements for the permitted uses, yards, and maximum height," and "it was apparent that one community could cut and paste into its local code another municipality's zoning ordinance" (p. 5).

The Euclidian system was intended to provide certainty through bureaucratic means. It allowed for very limited discretion, except through variances, a tool designed as a "safety valve" for the system and meant to be used as little as possible. The ordinance and the map were enough to deduce a dichotomous predictable decision, i.e., a use in a neighborhood was either permitted (as of right) or prohibited. The administrative zoning staff members were expected to apply these decisions as neutral bureaucrats without any bargaining or negotiation.

As early as 1966, Babcock noted that except for its intended protection of single family detached dwellings, "zoning technique has undergone changes so dramatic as to make almost impossible a comparison of the device as it appeared in the 1920's with its progeny four decades later" (pp.3-4). New mechanisms dissolved the dichotomy of permitted and prohibited uses, increased the discretion of the local staff, and relaxed the mandatory specifications of the rules (e.g., assigning only densities and uses for PUD districts rather than drafting lot-by-lot bulk controls).

First, the variance became widely used to permit certain prohibited uses. Then, after WW II, the special-use permit (also called conditional use) introduced the idea that certain uses are not by right, but subject to the review of local authorities. These two mechanisms increased (though in a limited degree) the freedom of local staff to accommodate different interests.

The concept of a floating zone, another tool introduced in the postwar era, started another informal process, namely bargaining. A floating zone is "a zoning district whose requirements are fully described in the text of the ordinance but which is unmapped." The permission to anchor the use onto land is given by the local authority upon the request of the developer. This technique became popular especially for large-scale shopping centers and industrial or business parks (Meshenberg 1976).

Having evolved from the concept of a floating zone, the Planned Unit Development (PUD) provided an important alternative solution for drafting lot-by-lot bulk controls. The PUD introduced two changes: (1) it relaxed the written mandatory specifications such as bulk regulations, and, at least in the PUD scale, it provided flexibility in building and street configurations; and (2) it provided an alternative process to design the development. Barnett (1982) explains, "in a PUD, only the major streets remain as ordinarily mapped; the subsidiary access and collector streets are planned at the same time as the buildings. The result is a street layout much more closely related to both the natural landscape and the design of the buildings than the 'objective' gridiron plan and the lot-by-lot development fosters" (p.67-68). From a legal perspective, "essentially [a] PUD is a method of flexible land subdivision that permits use of newer design concepts, such as integration of varied types of land uses, cluster development, and communal open space" (Lai, 1988: p.153).

Another tool that has radically changed the formal framework of zoning is special zoning districts. The special zoning district is "a district established to accommodate a narrow or special set of uses or for special purposes” (Meshenberg 1976). There is an intentional ambiguity in this definition; it is intended to facilitate different interpretations according to different interests. Meshenberg (1976) notes that "the establishment of special districts must have an appropriate police power basis, and there should be a reasonable market demand for the permitted uses . . . ." In other words, in special zoning districts, which uses and developments can be permitted depends on the discretion of local authorities and on the developerÕs ability to negotiate. Especially in the 1970s and increasingly in the 1980s special districts became popular. New York City was one of the pioneers in designating special districts. In describing the example of Manhattan's Special Theater District, Barnett (1982) signals some concerns regarding fairness and due process:

The Theater District Legislation had set up a framework

for negotiation between each individual developer and the Planning

Commission. Because the design of theaters involves so many complexities

and variables, it would have been difficult to draft any other

kind of legislation for the district. Its special permit procedure

has drawbacks, however. It allows the city government considerable

discretion, which makes it difficult for the public to be certain

that it knows what is going on (Barnett 1982, p. 79).

In sum, zoning, which was originally intended to

function as an automatic "traffic light," has been transformed

over the past seven decades, into a mechanism that now requires

"police" to direct the traffic. Are these changes in

the concept and implementation of zoning positive or negative?

Is it good policy to provide discretion to enable different solutions,

or is it better to depend on simple, abstract, formal controls

and therefore know exactly what to expect from future land use?

These questions are central to planning theory and methodology.

They represent the tension between the advocates of formal and

informal control. Babcock (1966) argues that the relaxation of

zoning weakened its ability to stand against various private interests

and zoning became easily trimmed to the wind, in the windy chaos

of the land market. On the other hand, Smith (1983) suggests that

zoning will be stronger as the system provides more discretion

and local autonomy, and as it gains ability to involve the different

interests in the community.

b. Postmodern assumptions for territorial controls

The criticisms voiced against modernism’s call

for technocracy and instrumentally rational planning ultimately

triggered a paradigm shift from technocratic objectivism toward

a plurality of paradigms (Habermass 1970). The emerging paradigms

of place, sustainability, and participation challenge the appropriateness

of the rational model to address contemporary issues such as loss

of sense of place, environmental integrity, and local autonomy.

These constructs are interpreted in different ways depending

on whether the interpreter makes formalist or informalist assumptions

(see Figure 1).

Place paradigm:

The construct of place (as the antithesis of space) refers to the meaning and significance of particular place experiences that abstract spatial analysis cannot capture. This perspective, especially the concept of authentic place identity, has been useful in contrasting modern international-style architecture to vernacular and pre-modern urban environments. Numerous articles have contrasted "sense of place," which implies warmth and empathy, with impersonal, generic, and alienating modern environments built since the 1920s (Alexanderet al 1987; Calthorpe 1986; Jacobs and Appleyard 1987; Norberg-Schulz 1985; Trancik 1987; to name few among many others). White (1991) argues that unlike the separation of uses in traditional zoning, variety of uses in a given place supports place-bound socialization and thus encourages

FIGURE 1

ASSUMPTIONS IN FORMALIZATION AND INFORMALIZATION MOVEMENTS

collective place identity. Oldenburg (1988) studies places such as cafes, tea houses, bars, beer gardens, etc. -- where place-bound social contacts occur -- and suggests that the existence of social activities in these places, which he calls "third places," increases their significance in daily life cycles; it adds authenticity and increases peopleÕs attention and care for "place" in general.

The notion of "care" for places implies protection, which is the basis of many preservation-oriented control mechanisms. As the paradigm evolved, the claims of authenticity, place identity, and sense of place became legitimate grounds to apply public control over private property. Aesthetics, as an inseparable component of the experiential framework of place interpretations, also became legitimate grounds for regulation.

What forms of control do these grounds indicate or require? So far the place paradigm has been supported by objectivist, subjectivist, and intersubjectivist interpretations. The oppositions among these views are significant within the paradigm, and for design review, because each interpretation calls for a different form of control.

The objectivist view claims that places possess certain qualities or properties independent from people's perceptions and attitudes. These qualities may be identified as authenticity; they may give the place (or object) a special character, a sense of place, or aesthetic ambiance and are assumed to be in the place waiting to be appreciated. Once these values or attributes are identified, it is possible to formulate rules to preserve them as "resources." Various objectivist studies have attempted to define and record the visual qualities of natural landscapes (Morisawa 1971; Litton et al 1974; Polakowski 1975; Riotte et al 1975; also, for a review see Brooks and Levine 1985). Similarly, most historic preservation guidelines are based on the concept of authenticity as an inherent quality that can be defined in terms of visual attributes (such as style and features of historical buildings). Within this framework, the introduction of new concepts like place character or identity acknowledges the existence of additional qualities embodied by certain places, waiting to be identified, measured, and preserved.

The subjectivist view, on the other hand, denies that place character, identity, or aesthetic qualities can exist apart from people's emotions, sentiments, and personal memories. It therefore provides no grounds for public control over private property for the purposes of preserving these qualities of place. After all, a place can be meaningless, faceless, and ugly for some, but still be meaningful and aesthetically pleasing for others: "beauty is in the eye of the beholder."

The intersubjectivist view incorporates the basic

subjectivist assumption that there cannot be a priori place categories

such as “authentic” or “artificial,” apart

from people's emotions, memories, and attitudes. But it differs

from the subjectivist view by asserting that the values people

attach to places are socially constructed and collectively shared.

The public can agree that certain places or objects -- buildings,

plazas, scenic views, valleys, mountains --do symbolize certain

values or reveal significant attachments ans are therefore worthy

of preservation (Appleyard 1979). Moreover, in the face of rapid

environmental change, people may identify their rootedness with

these places, so that infringements upon the places or objects

threaten the values and identities. Costonis (1989), one of the

major supporters of this view, calls these objects "icons."

He claims that the disturbance of icons by the intrusion of new

developments -- aliens-- is tantamount to the destruction of what

those icons symbolize:

Other paired icons and aliens are readily called

from court reports of the last quarter-century's battles. Illustrative

are a pump storage plant (alien) scarring the Hudson Valley's

Storm King Mountain (icon); a 307-foot tourist tower (alien) desecrating

the Gettysburg National Cemetery (icon); a strapping office complex

(alien) soaring above and demeaning the nation's Capitol (icon);

power transmission lines (alien) contaminating the view across

New Haven Bay (icon); Marcel Breuer's hard-edged, fifty-two-story

tower (alien) heckling [Manhattan's] Beaux Arts Grand Central

Terminal. (Costonis 1989, p.57).

The associations that make a place or an object an icon are not permanent; they are subject to change. At the time of construction, both the Eiffel Tower and the Golden Gate Bridge were seen as alien by many people. Moreover, even the meaning of shared place memories can change in time. Some memories are Òbetter forgottenÓ; disaster, or a shameful and horrible event, such as a massacre, can change the meaning of a place and create a collective discomfort.

The intersubjectivist view calls for a dynamic form

of control. It assumes that development is not disturbing unless

it is perceived as alien. Furthermore, there is a tolerable degree

of intrusion by aliens, and collective sentiments defining this

tolerance can also change in time. Therefore, public regulation

for preservation cannot depend on bureaucratically applied static

standards. Instead, preservation of icons requires continuous

reinterpretation of changing collective sentiments. In other words,

the intersubjectivist interpretation of the place paradigm calls

for informal controls based on social communication.

Sustainability paradigm

In the history of American conservation, the opposition between "resource conservation" and "nature preservation" goes back to the turn of this century. The "resource conservation" movement advocated “wise use” of natural resources in a utilitarian and efficient way; the "nature preservation" movement advocated preservation of natural areas untouched, so that humans might appreciate and learn from the sublime quality of nature (Koppes 1987). The resource conservation advocates supported rational and scientific resource management within agencies like the National Forest Service; the nature preservationists introduced ethical principles such as respecting wildlife for its own sake, concerns that guided the establishment of the National Park Service and later the Fish and Wildlife Service. In the 1960s and 1970s, the environmental movement gained a large, popular basis and the concept of sustainability was introduced into social discourse, two distinct views of sustainability emerged with differing implications for design review.

The first view focuses on the ecological management of biotic systems. It advocates the control of resources and management of ecosystems in a coordinated and scientific manner (e.g., Ahern's management model to implement an "extensive open space system,Ó in Ahern 1991). This view encourages centralized management. In the face of the rapid destruction of ecosystems it places controlling human activities ahead of equity and cultural diversity. It depends almost exclusively on the scientific method to collect information and diagnose systemic problems, and on technocratic, rational planning to control land use. It advocates standards and regulates compliance through an auto-administrative bureaucratic system.

The second view emphasizes the linkages among cultural,

biotic and abiotic aspects of environmental relations. Sustaining

cultural diversity is an aim inseparable from sustaining biodiversity.

For example, Greider and Gorkovich (1994) emphasize the importance

of cultural definitions in assessing environmental impacts. This

view contextualizes environmental problems in a broader systematic

structure where social and cultural processes form the significant

part of systemic relations (Nassauer 1992; Thorne and Huang 1992).

In this view, sustainability requires, first, a shared understanding

of environmental problems and a public commitment to the goal

of sustainability (Sancar et al 1992). Although it was initiated

at the federal level and was criticized as being "toothless,"

the 1969 National Environmental Protection Act's requirement for

the preparation of environmental impact statements effectively

initiated a local argumentation process. For example, the Òstatement

of public purpose" section requires an exploration of contexts

that in turn establishes a clear link between public goals and

local ecological processes, thus increasing public understanding

and establishing a common ground among the different parties before

a major federal project can be implemented.

Participation paradigm

Among the three paradigms, participation is the one that directly opposes authoritarian, technocratic, formal control over social actions. The initial enthusiasm for the possibility of social engineering and scientific management of social systems died a few decades after WW II, and planners and others began to challenge the theoretical basis of such planning. Rittel and Weber (1973), for instance, suggested that it is impossible to follow the rational model in dealing with planning problems, because these types of problems are "wicked." Contrasting the viewpoints of residents of Boston's North End with the views of planners and bankers, Jane Jacobs (1961) challenged the assumption of value-neutrality by asserting that what the technocrats say and what people want are often times different. The equity planners questioned the appropriateness of externalizing "value and ethics" and the notion of a value-neutral planner (Davidoff 1965, Krumholz 1982). Hasson and Goldberg (1987) argued that "separation of rationalism from ethics is more imagined than real" (p.15). On the issue of implementing the rational procedural model, Lindblom made a convincing argument that the planning process both is, and ought to be, incremental rather than rational (Lindblom 1959), and suggested that coordination can be achieved without a central authority, i.e., "people can coordinate with each other without anyone's coordinating them" (Lindblom 1965, p.3). Addressing both the procedural and substantive issues, Forester (1988a) suggested that planners face questions of both equity and efficiency and deal with both uncertainty and ambiguity in everyday practice. Forester (1988a) argued that the misleading separation of facts and values puts planners in a position where practical issues are reduced to technical matters. Elsewhere Forester (1988b) suggested that reducing political and ethical issues to technical ones and manipulating public ignorance in defense of professional power creates unnecessary dependency, generate unrealistic expectations, and immobilize and depoliticise the general public.

The basic assumptions of the "participation"

paradigm stand on these and similar observations. Participation

is crucial in achieving effective planning. Moreover, the paradigm

sees participation as a condition to increase the quality of life.

Smith (1973) suggests that participation increases the effectiveness

and adaptivity of planning and design and the flexibility and

stability of society. The paradigm also assumes that participation

is both a means to obtain higher goals, such as social and environmental

justice, and a goal in itself. Participation should widen the

circle of citizens who represent the breath and diversity of a

community engaged in a collaborative dialogue throughout the planning

and design process (Sancar 1993).

c. Dynamics of informalization and centrality of argumentation in design review

The postmodern worldview calls for land-use controls that reflect collective expressions of place attachment and allow for simultaneous resolution of equity and environmental problems by ensuring meaningful participation of the public in land-use decisions. We suggest that this worldview implies a particular notion of "design quality" that is based on two criteria: representativeness and responsiveness. Representativeness refers to how successful the design is in accommodating collective place-related emotions, symbolic attachments, and environmental concerns as they are expressed by different interest groups. Responsiveness refers to how succesful the design is in responding to the particularities of the design context: the site, the surrounding land-use patterns, climate, environmental features, etc. Representative and responsive design is rich and diverse -- neither monotonous nor chaotic.

Such a definition of design quality indicates a

need for informal controls that are implemented with a high level

of discretion and communication in design review. On the other

hand, informalization opens the door for potential abuse of discretionary

power. Here we explore this issue of accountability by describing

and contrasting the dynamics of non-discretionary systems with

those of discretionary systems with and without public participation.

Towards a discretionary, yet accountable design review

As Booth (1989) suggests, rules work better when a clearly stated objective is shared by all participants. However, it is hard to formulate general substantive standards to achieve design quality. Universally applicable formal rules, such as general bulk controls, are likely to fail in achieving good designs. Booth (1989) argues that simple formal rules are at best limited to functional or utilitarian objectives and limit diversity of expression and design quality. In other words, simple substantive rules are weak in responding to the complexity of specific situations. Thus, in time, the rules become complex and detailed during the course of design review practice.

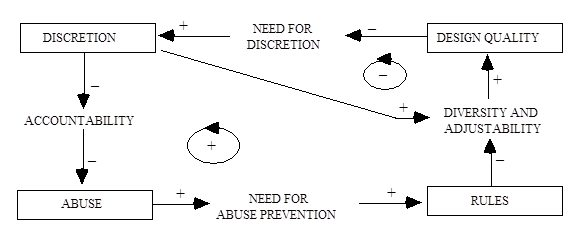

When regulations are too complex and detailed, however, their objectives become obscured and they can be easily trimmed to the wind. In Booth's (1989) terms, "the more rules there are, the more there are occasions to depart from them" (p.409). As the objectives behind the rules get obscured and the number of abuses increases, a need for simplification emerges. Consequently, these relations form a cycle (Figure 2). In this cycle, as the rules are simplified out of the concern for accountability, design quality continues to decline; or, as the rules get more detailed and complex, the chances of abuse increase.

In the absence of discretion the only way to overcome the problem of adjustability is to increase the complexity of rules. Therefore, if one needs to avoid complex rules, discretion becomes an essential prerequisite to accommodate diversity in design. As discretion enters the system, planning and design regulations begin to employ more and more procedural rules. Figure 3 illustrates the dynamics of a control system that allows discretionary decisions. In this system,

FIGURE 2

DYNAMICS OF NON-DISCRETIONARY REVIEW SYSTEMS

FIGURE 3

DYNAMICS OF DISCRETIONARY REVIEW SYSTEMS

Note: In these pictures, positive signs (+) indicate parallel increase or decrease, i.e., as x increases, so does y (or as x decreases, so does y); the negative signs (-) indicate increase or decrease in opposite directions, i.e., as x increases y decreases or vice versa. The negative cycles refer to self-regulating cycles, the positive cycles refer to amplifying cycles.

discretion affects design quality by influencing its level of diversity. This creates a self-regulating cycle. Discretion provides flexibility, so decision makers may respond to the particularities of the context more easily. Moreover, use of discretion allows the system to accommodate higher levels of communication; it allows reviewers and applicants to start an argumentation process during the design review.

Discretion enables design to be more responsive, but it doesn't guarantee that reviewers and designers will better respond to the context. Similarly, discretion allows reviewers to involve in argumentation, but it doesn't guarantee that such argumentation will improve design.

On the other hand, in discretionary systems reviewers may use their discretionary power in an authoritarian or capricious way. Therefore, an increase in discretion increases concerns about accountability. Introducing substantive formal rules and standards to the system solves this problem by forcing reviewers to provide equal treatment in design review. On the other hand, standards limit flexibility in decision making: they diminish the reviewers’ ability to be responsive. These two consequences of discretion (increasing responsiveness, and causing concerns about accountability) define two loops, one positive, the other negative (Figure 3). When the positive loop becomes dominant, rules become complex, abuses increase, and design quality diminishes; when the negative loop becomes dominant, flexibility of decision making increases, and so does the likelihood of achieving better designs, until questions of accountability arise.

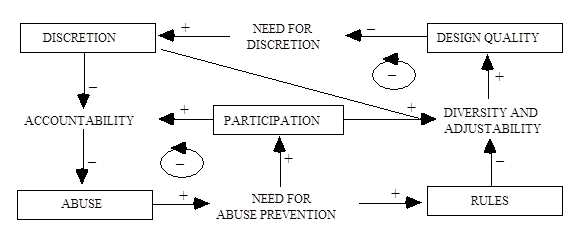

Participation by different interest groups in design review processes can make the system accountable as well as increase diversity in design. Figure 4 illustrates the dynamics of such a review system, where public participation creates a second self-regulating loop that controls the degree of abuse and accountability.

However optimistic this picture is, the success

of participation in providing accountability depends on the communication

between parties. Many communities today rely upon public hearings

and other similar mechanisms to receive public input into design

review processes, but in many cases these discussions are frustrating

for developers, designers, and the general public because they

lack methods for reaching a common understanding of issues or

mechanisms to increase the effectiveness of communication. When

public participation is ineffective, the effect of the self-regulatory

loop decreases and concerns about accountability and abuse of

discretionary power remain. As a result, often the review system

tends to limit administrative discretion and formalization is

maintained.

FIGURE 4

DYNAMICS OF DISCRETIONARY REVIEW SYSTEMS WITH PARTICIPATION

Note: In this picture, positive signs (+) indicate

parallel increase or decrease, i.e., as x increases, so does y

(or as x decreases, so does y); the negative signs (-) indicate

increase or decrease in opposite directions, i.e., as x increases

y decreases or vice versa. The negative cycles refer to self-regulating

cycles, the positive cycles refer to amplifying cycles.

Another alternative, as we suggest here, is to find

ways to increase the effectiveness of public participation. Thus,

in facing concerns of accountability there are two choices: (1)

formalization, i.e., introducing universally applicable rules

(and giving up diversity in design), or (2) informalization, i.e.,

increasing communication, sustaining argumentation, and finding

more effective participation mechanisms (and not giving up diversity

in design).

Rational argumentation and universal pragmatics

For Goldstein (1984), a significant difficulty in achieving rational argumentation is that utilitarian reasoning may dominate argumentation when there are competing arguments presented by different wordviews. He states that planning and design arguments use primarily three types of reasoning: utilitarian reasoning (instrumental rationality), systems reasoning, and procedural reasoning (deontological, value-based ethical reasoning). He suggests that there is a hierarchical relationship between these reasonings because of the norms they indicate. According to this hierarchy stability and order (systems reasoning) comes first, then comes efficiency (utilitarian reasoning), and finally comes fairness (procedural reasoning). The questions of whether such a hierarchy exists and whether utilitarian and systems reasonings can dominate procedural reasoning in planning and design discussions need further empirical research. There is some evidence that planners do not always use systems or utilitarian appeals. Howe (1993), for instance, shows that a deontological ethical approach is very common among the 96 planners she interviewed in four states. Similarly, Beatley (1994) argues that deontological value-based ethical reasoning is the dominant reasoning guiding many environmentalist movements and preservation-oriented land-use decisions.

Majone (1988) argues that it is not instrumental rationality nor scientific validity but the ability to persuade, i.e., rhetoric, that matters in guiding argumentation processes. That is, systems or utilitarian reasoning cannot dominate the discussion unless the argument itself is presented in a persuasive way. Moreover, persuasion is a matter of not only logic but also of craft. He further suggests that value judgments are an inseparable part of rhetoric. Majone's approach, which emphasizes the role of rhetoric and persuasion in argumentation, decreases the concerns about a specific type of reasoning dominating the argumentation. On the other hand, it underlines some other difficulties in achieving effective argumentation: Parties may, and do, manipulate the communication.

Forester (1989, 1993) argues that the problems arising in argumentation processes in planning practice are due to what Habermas calls "distorted communication." Habermas (1979) adresses the question of "distorted communication" by introducing the concept of "universal pragmatics": certain standards generally taken for granted in common speech where mutual understanding is achieved. Successful social communication assumes (a) comprehension, i.e., the proper use of language to communicate, (b) sincerity, i.e., one needs to be sure that the other party is sincere, (c) legitimacy, i.e., the speaker's social position should be legitimate in the context of speech,and (d) truth, i.e., one must assume that the facts presented by a speaker are true and that the speaker's intention is to provide a factual basis for the communication. According to Habermas (1979), when one fails to make any one of these assumptions communication cannot take place. On the other hand, when the listener is convinced about these standards, i.e., when he or she makes these four assumptions confidently, the outcomes are attention, trust, consent, and belief. Distortion occurs when parties manipulate these assumptions to avoid effective communication. Sometimes it is desirable to avoid communication. For example, in bureaucracies, avoiding communication is a way of dealing with various pressures. Distortion occurs, for instance, when a speaker intentionally uses complicated terminology that would hinder easy comprehension; or when his or her expression and attitude give the impression that he or she is not sincere; or when he or she intentionally distorts the facts to misinform the listener.

Forester (1989; 1993) argues that some of these distortions are systematic, i.e., they are consequences of institutional and bureaucratic structures. Dealing with systematic distortions is difficult since they reflect power structures at higher levels. But there are also some other distortions, he argues, that are easily avoided. Officials may even distort communications unconsciously; they may use unnecessary technical language, they may seem uninterested, and the listeners may think that the planners are presenting evidence by choosing facts arbitrarily. These are "unnecessary distortions."

Given that argumentation is an essential part of

design review processes, the question is, how does one overcome

systematic distortions in communications? What are the ways to

achieve legitimacy, comprehension, sincerity, and truth in argumentation

in the context of design review?

Centrality of designerly argumentation in design review

Forester (1985) suggests the metaphor of “designing as making sense

together in practical conversations”:

Whether design originated in intuition or inspiration,

the unconscious or acculturation, the voice of a Muse or another

creative impulse, design materializes and is realized through

deeply social processes of review, evaluation, criticism, modification,

partial rejection, and partial adoption. . . . If form-giving

is understood more deeply as an acitivity of making sense together,

designing may then be situated in a social world where meaning,

though often multiple, ambigious, and conflicting, is nevertheless

a perpetual practical accomplishment (Forester 1985, p.14).

In public forums, design charettes, or design review negotiations, participants including designers engage in an argumentation process where new ideas emerge, and then are negotiated and integrated into a design. Thus, argumentation and design become inseparable processes.

The significance of designerly argumentation in design review is twofold. First, designerly argumentation is possible only within a discretionary and participatory design review structure. In earlier work, one of the authors suggests that the following principles are crucial: integration (integration of planning and design in design review), interpretation (acknowledgment of the situational nature of knowledge in design review), improvisation (spontaneous coproduction of design solutions), participation (representation of all interests), and learning (reaching a mutual understanding and establishing a new knowledge base) (Sancar, 1993). Designerly argumentation is one way to implement these principles. Second, a productive designerly argumentation has the potential to overcome most of the distortions in communication--distortions in comprehension, sincerity, legitimacy, and truth.

Comprehension: In addition to spoken language, visual presentation techniques (plans, sections, perspectives, birds-eye views, diagrams, sketches, etc.) also play a crucial role in designerly argumentation. (Although there are some difficulties in interpreting these representations for lay participants, various techniques to ease this problem have been proposed [e.g. Craighead 1991; Yaro et al 1993].) These techniques can help to materialize the abstract arguments by vividly displaying the consequences of planning strategies. Design arguments provide a direct and instantaneous comprehension that no verbal abstraction can provide. The rules and controls become visible and comprehensible, preventing many distortions that might be caused by complicated legal language or detailed dimensional standards.

Sincerity: In designerly argumentations, especially in forums where new design ideas emerge through a critical discussion of proposals, the process fosters sincerity on the part of all parties. Participants express their concerns and suggest new ideas, and these suggestions encourage improvisation. The inputs are materialized in design, and participants can see the outcomes and intervene accordingly. This spontaneity and sense of producing something together has the potential to establish sincerity among participants that would be difficult to achieve in other forms of argumentation.

Legitimacy: When there is no agreement about the various parties' positions and status, it becomes hard for them to recognize each other's speech as significant and each other’s arguments as valid. In the absence of such agreement, negotiating and resolving the issue of each speakerÕs legitimacy becomes an important part of the communication (Forester 1985). In conventional public review meetings, the role of planners, reviewers, designers, developers, and other participants are rarely well defined. Are residents' comments in a review commission's meeting binding? To what degree do the reviewers have the authority to alter the project? What is the authority of the designer? Usually there are no clear answers for these and similar questions in design review practice. Often the roles are negotiated together with the design itself. Nevertheless, designerly argumentation can facilitate such negotiations. For example, during the review process social relations and participants' roles can be materialized. In an instantaneous co-production process, designers (or reviewers) can use their abilities to synthesize and to integrate suggestions of other participants, and develop a design that makes sense to everybody. By this process, not only do they establish their roles and their own legitimacy, but they also show that the roles of other participants have been recognized and that participants' concerns have been crucial in developing the design one step further, and thus establish their legitimacy.

Truth: In any argumentation process arguments present certain facts as evidence (Majone 1989). These facts provide grounds for the argument (Goldstein 1984). Through these chosen facts, an argument establishes its own relation to reality, thereby defining its context. In an argumentation, if the listener thinks that the speaker is distorting the facts and obfuscating certain relations in order to support an argument, the listener disbelieves in the speaker's evidence. In designerly argumentation, design arguments put forth evidence by presenting facts and relations in reports, charts, and other verbal media; as well as spatial graphics such as maps, plans, and images. For example, an open space master plan for a town justifies the proposal by explaining that "we need X amount of open space set aside because of this and that reason," and by showing exactly what it would be like to have an open space system such as the one that is proposed in detail. The drawings, in other words, clarify the meaning of the statement Òwe need open spaceÓ and prevent potential misunderstandings.

Achieving and sustaining a productive designerly

argumentation in order to provide an effective public participation

is not an easy task. How central a role does designerly argumentation

play in design review? Do the participants participate in designerly

argumentation at all? One may expect that they do, to a certain

point, especially in discretionary systems. If so, to what extent

are the principles mentioned above achieved in practice? What

are the major difficulties that reviewers face in achieving or

sustaining designerly argumentation in design review? Having

formulated these questions we were able to explore the place of

designerly argumentation in land-use review programs in small

towns in Wisconsin. Firstly, through a survey questionnaire,

we identified planners’ attitudes regarding discretionary

review systems. We then interviewed a number planners to understand

the actual dynamics of the reviews. We also studied a number

of successful cases from Boulder, Colorado. By analyzing these

cases, we were able to identify difficulties and impediments in

achieving and sustaining a designerly argumentation process as

well as factors that contribute to its success. We concluded

that three key principles should guide design review: (1) ensuring

designerly argumentation, (2) integrating planning, design, and

design review, and (3) establishing a consolidated administrative

structure to coordinate the various layers of review processes.