The Rise

and Fall of People Express: A

Dynamic Resource-Based View

John Morecroft, London Business

School

Abstract

The

People Express case (Whitestone 1983) and simulator Sterman

(1988) have been widely used to introduce the pitfalls of fast growth

strategy. In real life People Express

airline was a fascinating case. The

company grew from obscurity to industry prominence in a period of only five

years against powerful rivals. Dramatic

growth was followed by equally dramatic demise.

The

reason for the company's rise and fall is usually explained as a variant of the

growth and underinvestment syndrome.

Service capacity failed to keep pace with the growth of flights and

passengers and so, ultimately, the service reputation of the business was

destroyed. At first glance this argument

seems compelling. But it fails to

explain why, in real life, a company could have made such a fundamental

strategic error without realising it.

The

paper outlines a method for analysing the rise and fall of People Express in

steps that reveal the dynamic complexity of the business. The approach builds on two influential sets

of ideas taken from the strategy field and unites them with conventional system

dynamics: 1. the so-called resource-based view of the firm; and 2. the dominant logic of the firm.

The first step in applying this "dynamic resource-based view" is to

identify the tangible and intangible resources of the fledgling airline, such

as planes and service reputation. The second step is to examine the dominant

logic of the policies that control the expansion of resources. A combination of partial and whole model

simulations then reveals why the dominant logic remains unchanged as the firm

loses and destroys its competitive advantage.

The

paper ends by outlining some exciting areas for future research that may be

amenable to a dynamic resource-based view of the firm.

People Express: Growth and Underinvestment, But Why?

In

The Fifth Discipline Senge 1990 outlines a theory of what

happened at People Express that builds on the growth and underinvestment

archetype (chapter 8, pages 130-135). At the heart of the theory is

underinvestment in service capacity.

Moreover (and most important for such a theory) is the proposition that

underinvestment was very difficult for managers at People Express to discern at

the time the company's spectacular growth was taking place. Investment in service capacity is driven by a

'perceived need to improve service quality' and fails to keep pace with the

growth of passengers. But

why? Senge

hints at two reasons (each informed by feedback thinking and the chosen

archetype): 1. service capacity

(controlled by a balancing loop) did not keep pace with the growth of planes

(controlled by a powerful re-inforcing loop); and 2.

(implicitly) this imbalance was masked by tremendous

growth in headcount which did not fully translate into corresponding growth in

service capacity. Nevertheless one is

left wondering why the company persisted in its aggressive fleet expansion and

why (in its hiring policy) the company did not appreciate that headcount and

service capacity are fundamentally different.

To

examine these anomalies we turn to two sets of ideas from the strategy

literature. The first is the so-called

resource based view of the firm which explains differences in firms'

performance and competitive position in terms of endowments of critical

productive assets or resources (Barney 1991, Foss et al 1995). In particular we draw on a dynamic view of

resource accumulation developed by Dierickx and Cool

1989 which makes the same distinction between stocks

and flows (or levels and rates) as found in system dynamics. The second idea is the notion of dominant

logic which provides a cognitive/behavioural explanation for different

managerial styles of resource management (originally introduced into the

strategy literature by Prahalad and Bettis 1986 as a way of explaining differences of

performance in diversified firms). Dominant logic is very similar to policy

logic in system dynamics (Morecroft 1985 and 1994).

Resource Accumulation - the Time Dimension

of Strategy

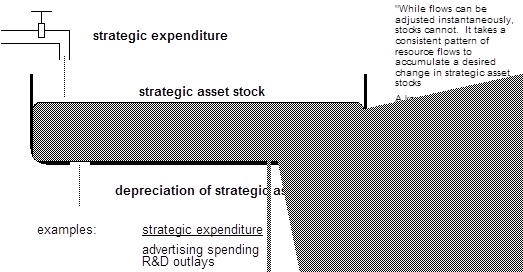

Figure

1 below will come as no surprise to system dynamicists. It is the familiar bathtub image of levels

and rates. Here the image is being used

to depict the accumulation of a strategic asset stock as the result of an

inflow of strategic expenditures and an outflow of depreciation. This icon of stock accumulation is a key part

of Dierickx and Cool's contribution to the resource-based

strategy literature. In a nutshell they are saying that in order to understand

resource endowments (and therefore competitive advantage) one has to understand

the process of resource accumulation.

"A key dimension of strategy is the task of making appropriate choices about

strategic expenditures with a view to accumulating required resources and

skills". At People Express

strategic asset stocks (or resources) include tangibles such as the fleet,

staff and customers as well as intangibles such as service reputation and staff

morale. The success (and sustainability)

of People Express' competitive strategy then depends on the balance of

resources achieved in relation to competitors.

Figure

1: Visualising the Accumulation of

Resources, First Step Toward a Dynamic Resource-Based

View of Strategy

Resource Management and Dominant Logic: a Framework for Understanding Dynamic

Complexity at the Level of Resources and Policies

Dierickx and Cool's ideas have

been important in the strategy literature because they directed attention away

from static endowments of resources toward the dynamics of resource

accumulation. However, their thinking about flows is framed in terms of

strategic expenditures and does not adequately deal with the managerial logic

that drives resource management. In

People Express we really want to know why the fleet of

planes grew at the rate it did, and why service capacity failed to keep pace with the

growth of either planes or staff (headcount).

Once we can understand the logic driving resource accumulation then it

should be possible to explain how competitive advantage turned (invisibly) to

disadvantage.

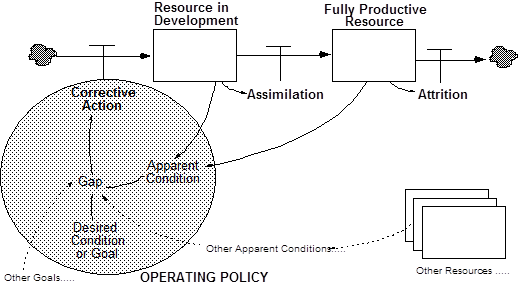

Resource

management fits naturally with resource accumulation in system dynamics. Figure 2 shows an operating policy for

resource management overlaid on a generic resource accumulation process

involving both a fully productive resource and a resource in development. The resulting stock and flow network is familiar

to all system dynamicists. The policy governing corrective action

contains information feedback and goal adjustment that encapsulates the

dominant logic of resource management (Forrester 1961 chapter 10, Morecroft 1994, Sterman

1989). The terminology of the diagram

needs no further explanation (at least for ISDC 97 readers). Its power (for

dynamic theories of strategy) lies in its ability to represent both resource

accumulation (Warren 1997) and dominant logic.

When these two powerful ideas from the strategy literature are united

through the discipline of system dynamics and brought to life with simulation,

a versatile framework then exists to develop and test dynamic theories of

resource accumulation - including cases such as People Express where initial

success turns inadvertently into failure.

Figure

2: Operating Policy for Resource

Management - Goals and Information Feedback

Applying the Framework to People

Express

The

first step in a dynamic resource-based analysis is to classify resources into

tangible-intangible and managed-unmanaged.

For People Express the relevant information is in the case and it is a

matter of (modelling) judgement which of the many listed resources to

include. Obvious tangibles are planes,

staff and passengers. Intangibles

include service reputation and staff morale.

The classification into managed and unmanaged resources is quite subtle,

but it is vital because it is often unmanaged resources (usually invisible at

the operating level, and often intangible) that are

the undoing of an otherwise successful strategy of resource accumulation. Figure 2 above provides some clues of what to

look for in making the managed-unmanaged classification. For a typical managed resource there is

usually a clear desired condition or goal.

The apparent condition of the resource is often measurable. As a result the gap that drives corrective

action is objective and beyond dispute and the managerial feedback control

process is purposive and goal-directed.

A simple and familiar example would be a production policy that manages

factory inventory to a strict goal. If

all resources in a firm were managed with such ideal clarity (and if all

underlying goals were not only clear but also internally consistent) then an

effective resource strategy should emerge. However, in many cases key resources

are not well-managed, or not managed at all. There are many small hints and clues to

isolating unmanaged resources in practical situations. Often the resources are intangible or soft,

so that it is difficult to discern the apparent resource condition. The desired condition or goal may itself not be

clear or appropriate. The resource in

development may be invisible. In the

case of People Express unmanaged resources include potential passengers,

service reputation and staff motivation.

A

rough classification of resources leads to the second step of analysing

dominant logic. This phase of analysis

is demanding but also interesting because it reveals the managerial rationale

for the firm's continuing resource accumulation strategy. Let's start with the tangible resources at

People Express. What is the dominant

logic of fleet expansion? Such strategic

investment decisions could be governed by funding constraints, market share

goals, return criteria, demand forecasts, or staffing constraints. The dominant logic at People Express however

appears (between the lines of the case and video) to be CEO Don Burr's

ambitious personal growth target, stemming from his vision of industry revolution embodied

in the precepts of the company. Clearly

such logic is both powerful and persistent.

The imposition of Burr's dominant logic leads to reinforcing feedback in

the resource stock of planes.

The

dominant logic of staff expansion is quite different. From the case one gathers the impression of a

Human Resource VP insistent on high-quality recruits, carefully filtered (with

input from the top management team) and trained on the job. The imposition of

this dominant logic leads to reinforcing feedback in which the resource stock

of experienced staff is the principal determinant of hiring.

The

dominant logic of passenger growth is also noteworthy at People Express. Customers are a vital resource stock for all

companies. Some companies explicitly

manage customers: by setting sales targets; tracking customers in huge

databases; and implementing marketing programmes to eliminate any gaps relative

to goal. Other companies don't really

actively manage the customer base, but instead allow it to evolve from

advertising, word-of-mouth and churn.

People Express seems to have adopted an ambitious but essentially

unmanaged approach to growth of customers.

Deep price discounts coupled to targeted advertising unleashed a

powerful word-of mouth effect that caused a very rapid build-up of potential

passengers (those fliers willing to try People Express should the opportunity

arise). The imposition of this dominant

logic embodies reinforcing feedback characteristic of word-of-mouth.

The

resulting tangible resource system contains three reinforcing feedback loops,

each a compelling engine of growth, but each operating seemingly independently

to produce autonomous expansion of planes, staff and passengers. Partial model simulations reveal the power of

these growth engines to underpin the kind of spectacular growth achieved by the

People Express in reality.

Resource System and Baffling Growth

Dynamics

The

third step of the dynamic resource-based analysis looks to the behaviour of the

intangibles (service reputation and motivation) to explain the demise of People

Express and (more importantly) the invisibility of the company's mounting

resource problems. From the case it

appears that neither service reputation nor staff motivation is managed. This

observation is no surprise when one considers that almost all the requirements

for active resource management (in figure 2) are absent: operating goals are

not clearly defined; and the apparent condition of the resource stocks is

unknown (how to do get inside the mind of the customer to measure service

reputation, or into the emotions of staff to discern motivation?). So reputation and motivation just evolve from

operating conditions. Motivation

responds to a range of dynamic factors such as company growth rate and

profitability and then goes on to influence staff productivity. Reputation

responds (with a time lag) to the balance of flying passengers and service

capacity, while service capacity itself is a complex dynamic mix of the number

and blend of experienced and newly-hired staff as well as staff

productivity.

When

the three tangible engines of growth are out of step (and it would only be an

accident if they were exactly co-ordinated, since their dominant logic is so

different), then problems begin to accumulate in the intangibles. No management action is taken to fix these

problems because: 1. the unmanaged intangibles provide only weak signals to

rest of the organisation of latent growth stresses; and 2. the powerful dominant logic governing

tangibles is insensitive to such weak signals.

This seeming paralysis in the face of impending doom is symptomatic of

management under conditions of dynamic complexity

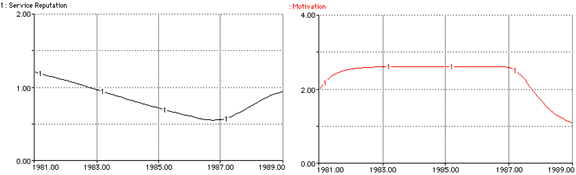

As

figure 3 shows, service reputation declines steadily for the first six years in

an 8-year simulation of People's growth strategy (the apparent recovery in the

last two years results from an unintended abundance of staff as disillusioned

passengers switch to competing airlines).

Motivation (though invisible and beyond direct management) remains both

steady and high for the first six years, underpinning People's competitive cost

advantage. But as the customer base

saturates and then collapses, the excitement and profit-lure of a fast-growth

enterprise evaporates. Employees are demoralised. Planes fly

half-empty. The company dies with

a configuration of resources (both tangible and intangible) that is markedly

inferior to its major competitors. There is no commercially viable route of

recovery from this resource trap.

Figure

3: Time Behaviour Charts of Intangible

Resources: Service Reputation and Staff

Motivation

Implications of a Dynamic

Resource-Based View of the Firm

The

paper presents a dynamic resource-based view of the rise and fall of People

Express. At the heart of this view is a

synthesis of two powerful and influential sets of ideas from the strategy

field: 1. resource accumulation as a way of understanding firms' resource

endowments and enduring differences in firms' strategy and performance; and 2.

dominant logic as a way of understanding firm-specific traits of resource

management as they affect firm performance.

System

dynamics is a natural way to unite these ideas.

Stocks and flows portray resource accumulation, while information

feedback and policies embody dominant logic.

The stock/flow and policy framework provides a versatile means of

visualising firms' resource systems and (through simulation) for understanding

the dynamics of strategy as it arises from underlying resource management

policies.

The

framework throws-up new vocabulary and concepts for analysing strategy and

business dynamics. Firms are viewed as resource systems. Resources can be classified into

tangible-intangible and managed-unmanaged.

Patterns of resource accumulation (both effective and ineffective)

result from firms' dominant policy logic for managing resources. Strategies

(like People Express) where failure follows dramatic success can be explained

in terms of flawed dominant logic for managed resources (operating goals and

feedback information that is inadvertently at odds with overall strategy),

along with unintended accumulations of invisible or unmanaged resources that

interact with managed resources in unexpected (and usually detrimental) ways.

The

framework has the potential to be applied in any areas where the ideas of the

original (quasi-static) resource-based view and/or dominant logic have taken

root. This potential is particularly

exciting for those working in system dynamics, because the resource and

dominant logic 'paradigms' are to be found at the heart of mainstream strategy

in areas such as competitive strategy, diversification, corporate portfolio

management (joint ventures and acquisitions), and international strategy

(geographical diversification). Until

now, most firm-related system dynamics has (like People Express) focussed on

single businesses. A dynamic resource-based view opens the door to the

intriguing and dynamically complex world of the multi-business firm with the

possibility of model-based contributions to the dynamics of diversification,

transformation and internationalisation.

References

Barney

J. 1991. 'Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage', Journal of Management, 17,

1: 99-120.

Dierickx

I. and Cool K. 1989. 'Asset Stock Accumulation and

Sustainability of Competitive Advantage', Management

Science, 35, 12: 1504-1510.

Forrester

J.W. 1961. Industrial Dynamics, Portland, OR: Productivity

Press.

Foss

N.J., Knudsen C., and C.A. Montgomery 1995. 'An

Exploration of Common Ground: Integrating Evolutionary and Strategic Theories

of the Firm', 1:1-17 in Resource-Based

and Evolutionary Theories of the Firm (Montgomery

editor), Boston: Kluwer.

Morecroft

J.D.W. 1985. 'The Feedback View of Business Policy and Strategy', System Dynamics Review, 1,

1: 4-19.

Morecroft

J.D.W. 1994. 'Executive Knowledge, Models and Learning', 1:3-28, Modeling for Learning Organizations (Morecroft and Sterman editors), Portland, OR: Productivity Press.

Prahalad

C.K. and R.A. Bettis 1986.

'The Dominant Logic: a New Linkage Between Diversity and Performance', Strategic Management Journal, 7,

485-501.

Senge

P.M. 1990. The Fifth Discipline: The Art

and Practice of the Learning Orgnaisation, New York: Doubleday.

Sterman

J.D. 1988. 'People Express

Management Flight Simulator', available from author, Sloan School of

Management, MIT, Cambridge, MA 02142.

Sterman

J.D. 1989. 'Modeling

Managerial Behavior: Misperceptions of Feedback in

Dynamic Decisionmaking', Management Science, 35, 3:321-339.

Warren

K. 1997. 'Building Resources for Competitive Advantage', Mastering Management, 591-598, London: FT Pitman

Publishing.

Whitestone,

D. 1983. 'People Express (A)', Case No. 483-103, Cambridge MA: HBS

Case Services.