FLEET DOCTOR TO AIRPOWER

2100

From Tailored Solution to Learning Environment

J.W. Kearney, M. Heffernan, J. McLuckie

Abstract

††††††††††† The Royal Australian Air Force

(RAAF) operates a fleet of 36 F-111 aircraft based at Amberley in South East

Queensland.† The fleet is a multivariate

system with complex dynamics constrained by economic and human resources. In

1994, the aircraft fleet was experiencing declining availability and

operational capability.† The

implementation of long term strategic planning was extremely difficult due to

the complexity of the system and the rotation of† military staff on a three yearly

basis.† To analyse the system, a dynamics

simulation model was developed in Ithink software

coupled with a database and graphics software.†

The model was then used to develop a fleet strategic recovery plan.

However the system learning gained through model development has since

dispersed and the need for an F-111 system learning environment was recognised.

††††††††††† Furthermore the Australian

Government Audit Office has recently investigated Defence preparedness. The

report 1 highlighted the same basic systemic problems as were found

in the F-111 fleet were more widespread and generic in nature.† To address the specific F-111 learning

environment problem, and to reinforce the system solution, a game has been

developed called Airpower 2100.† The game

was created to sensitise people to the interactions and dynamics involved in

managing a complex aircraft weapon system as well as

weapon system preparedness. The game play takes 3 hours and coupled with a

tailored education program aimed at developing better management strategies.

Evaluation of the effectiveness of the game is being monitored by a capability

based survey given before and after the game play.† This survey, similar to the College and

University Classroom Environment Inventory (CUCEI) model 2, measures

participants perceptions, attitudes and confidence in

their ability to control the weapon system after the gaming experience.

††††††††††† This paper will outline the movement

from a tailored system dynamics solution to addressing the generic learning

problem.† It reports the initial stages

of achieving a learning organisational culture and the implications for future

applications of these techniques.

Background

††††††††††† The RAAF utilise a fleet of General

Dynamics F-111 aircraft for strategic strike missions and reconnaissance. This

fleet consists of F-111C strike, RF-111C reconnaissance and F-111G

aircraft.† The F-111 fleet is currently

subject to a major mid life avionics modernisation

program and a number of ongoing less major capability enhancements.† The objective of fleet management is to

sustain current operational availability, be capable of escalated operational

demand and continually upgrade the weapon system capability. This task can be

represented by a complex interaction of logistics, maintenance, facilities,

human resources, and capital acquisition programs.

Strategic Analysis

††††††††††† In 1994 it was recognised that the

F-111 fleet was experiencing declining availability and capability with

deteriorating future trends.† In order to

analyse the system a strategic model of F-111 fleet operations was developed.

The model, entitled FleetStrat2020, investigates the interactions within the

system that were leading to reduced availability and capability. This model,

incorporating many assumptions, treats the F-111 system as one amorphous fleet

structure.† The model was used to derive

a set of strategic corrective actions to be applied to the F-111 fleet.† However, the strategic model was inadequate

for detailed tactical implementation of these actions and so further

development was carried out.

Tactical Analysis

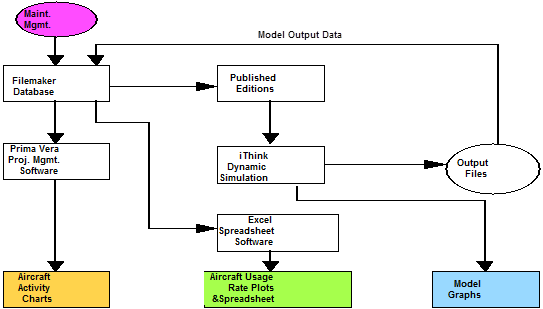

††††††††††† The next phase was the development

of Fleet Doctor“, an integrated F-111 fleet scheduling

tool. This tool incorporated a detailed Ithink

dynamic simulation model, a database engine, and graphical display software, as

shown in Figure 1. The simulation now modelled the F-111 fleet in detail with

all 36 aircraft and subfleets being steered through

characteristic logistics, operations, maintenance and capability upgrade

environments.† Building on the knowledge

gained from the strategic model the recovery strategies were simulated to

generate a detailed 10 year plan of fleet recovery. Fleet Doctor“ has been used for 18 months in fleet scheduling and has generated

improvements in fleet capability and preparedness 3.

Figure

1.† Fleet

Doctor Process Overview

Systemic Problem

††††††††††† The Australian Government Audit

Office report on the management of Australian Defence Force Preparedness found,

amongst other things, that resource implications of different preparedness

states were not adequately articulated.†

This replicated the systemic problem identified within the F-111 fleet

environment.† The report also stated that

management information systems were needed to measure achievement of

preparedness.† Whilst Fleet Doctor“ was capable of addressing this specific need for evaluating F-111

preparedness 4,†

it was concluded that the generic problems that were identified

in† the Auditors Report were similar to

those seen in the specific F-111 fleet.

Learning Environment

††††††††††† The tailored systems dynamics

solutions installed at Amberley for the specific F-111 fleet management were

developed by a dedicated team. The systems knowledge gained through the process

was only held by those within the team. This knowledge was being progressively

dissipated as military staff rotations took place. It was recognised that a

more generic learning environment would be required to retain this knowledge

and broaden the exposure of RAAF staff to the use of system dynamics for

effective weapon system management. To achieve this goal a prototype game was

developed along similar lines to The

Manufacturing Game† ‘† 5 and Friday Night at the ER† ‘† 6 . This

game, in part, replicated the interactions within the F-111 weapons system but

mimicked the underlying dynamic behaviour. The game, called Airpower 2100,

encapsulated the need for strategy development in achieving availability

targets. The script for the game introduces the players to environmental

changes that are outside the players control, are unscheduled and are similar

to the actual activities of the real environment. This includes rapid changes

in flying rate to meet contingencies and illustrates the concept of being

Ďpreparedí.

Survey

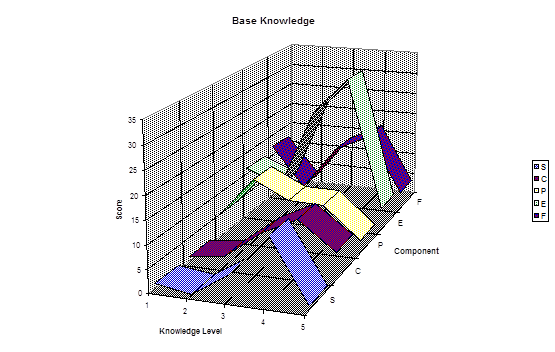

††††††††††† To evaluate the prototype game

representative cross section of† F-111 personnel, based at Amberley,

were surveyed prior to playing the game in order to establish a baseline

profile of their knowledge. The results of this survey were scored in order to

get an indicative profile of the players. Figure 2 shows this profile

indicating the pronounced lack of F-111 system† knowledge significant

deficiency in preparedness† knowledge and generally poor control††

knowledge. These results confirmed that a generic learning environment

was required before sustainable improvement would be achieved.

Legend††††††††††† :†

S=System† C=Control† P=Preparedness† E=Elements†

F=F-111 System

Figure 2:†† Base Knowledge Survey Results

First Trial

††††††††††† The game was trialed

at† Amberley on

23 April 1997 with players from F-111 operations, maintenance and logistics who

had been surveyed.† The Airpower 2100

game not only mimicked the complex dynamic behaviour of the system but players

interacted as if in the real environment. Some of the noteworthy benefits

observed were:

a.†††††††† All players gained insight into the

systemic problem.

b.†††††††† Most

players experienced a feeling of utter hopelessness when embroiled in the

system dynamics.

c.†††††††† No players questioned the limits of

their control within the game.

d.†††††††† Only one

player requested the same short term Ďget wellí method as used in the real

environment.

Trial Conclusions

††††††††††† Players found difficulty in

developing control strategies and were not sure of their level of control.† Subsequently it was decided to modify the

game script to incorporate a mid play break allowing

an opportunity† for

players to develop strategy. The game was effective in illustrating system

operation but was less effective in illustrating the concepts of preparedness.

Players could be asked about planning activities that they could do to meet the

increased operational effort†

3 game cycles ahead.

††††††††††† Greater learning could be gained

from game play if more opportunity existed for players to explore various

control strategies. This outcome would address the deficiency identified in the

survey.† To achieve this approach greater

flexibility within the game script for provision of extra resources was incorporated.

To force a better understanding of preparedness players needed to be coerced

into analysing their ability to meet projected future operational demand.

††††††††††† Four game boards with three players

on each board were used in the first trial.†

The knowledge gap of some players caused net game cycle rate to be very

slow. The game was modified to allow each game board team to cycle

independently if required. Some players clearly needed more time to assimilate

and comprehend the system dynamics. Some players had difficulty adjusting to

the paper recording system and it was concluded that a set of sample records

should be produced to accelerate game familiarity.

What the Critics Said

††††††††††† Airpower 2100 was seen as an

effective generic learning environment. The debrief survey indicated that all

players gained insight into the F-111 system and to a lessor

degree preparedness. To quote one respondent††

It didnít seem to matter how well I tried to

play everybody ended up in strife. Now I donít feel so bad.† One young F-111 pilot commented It should be played by the Air Commander.

There appears only one way to win and that is to reduce the flying commitment.†

Critical Observations

††††††††††† The military paradigm of not

questioning the bounds of the game was observed. Reducing the maintenance

interval was never questioned as a means of achieving better performance.† The game was extremely successful in

illustrating the effects of external influences on the stability of the fleet

system. Most players acknowledged that without observing the total system there

was no chance of achieving control. A significant benefit came from the

personal interaction of players who normally did not interact in the real

environment.

††††††††††† The first trial of the game also

provided feedback to the trainers.† There

was a need for discussion early in the game facilitation as an ice breaker. The

trainers realised that players had, in some instances, no base knowledge. A

need for more elaborate explanation of the game process was recognised.† The trainers also recognised that most

players need more time to assimilate their learning. The facilitation process

was adjusted accordingly.

Second Trial

††††††††††† A second trial of the game was

performed on 20 May 1997 at the Australian Defence Force Academy (ADFA) in

Canberra.† The game players were more

senior military staff and civilian personnel. The latter having no knowledge of

F-111 operations.† These players were

given the same pre-game survey as the first trial group. Similar results were

obtained.

Second Trial Conclusions

††††††††††† The adjustments made to the script

to allow for more time for strategy development were very successful.† The increased level of game facilitation made

initial game learning more accelerated and effective. The ability of individual

game teams to operate independently was also effective.† Higher levels of Systems knowledge and Preparedness

knowledge, evidenced in the pre-game survey helped the players develop strategy

and understand control more rapidly.

Post Game Debrief

††††††††††† Most players recognised the benefits

of team cooperation. The civilian players were able to see the relevance of

Airpower 2100 game in a non military environment.

Some notable quotes were:

Strategy requires experience and learning. The game provided both of

these opportunities.

Not quite as good as sex but nearly as complicated.

Reinforced my understanding

of the inherent complexity of the system and the need for mutual understanding

between elements.

I did not feel in control and this was just how I felt when working

in the F-111 environment.

It confirmed, in my mind, that this was not an easy system to

manage, especially if people wonít compromise.

Future Direction

††††††††††† The game has been refined to the

point where it can be introduced into the training and education processes

within the RAAF. The measurement of educational improvement will be monitored

using the College and University Classroom Environment Inventory (CUCEI) model.

This activity is scheduled for August 1997. Furthermore, a more generic version

of the game is being developed which deletes specific reference to the F-111

environment and to RAAF terminologies. This is to assist in playing the game in

a totally non-military context and to ďglobaliseĒ the game.

Conclusions

An F-111 system

learning environment has been developed which increases the level of

understanding and awareness of the F-111 fleer system dynamics. The learning

environment captures generic dynamics and has applicability that extends well

beyond the F-111 fleet and the RAAF.

Bibliography:

1. Commonwealth Government, The Auditor-General, Audit Report No 17, 2

April 1996, Management of Australian

Defence Force Preparedness, Australian Government Publishing Service.††††

2. Fraser, B.J., Treagust, D.F., Williamson,

J.C., & Tobin K.G. (1987). Validation

and Application of the College and University Classroom Environment Inventory

(CUCEI). In B.J. Fraser (ed.), The study of

learning environments, 5, 17-30.

3.†††††††† Kearney

J.W., M. Heffernan, J. McLuckie (1996), Australian

Systems Conference Proceeding, Applying

Systems Thinking to Aircraft Fleet Management,† Monash University, Melbourne.

4.†††††††† Kearney

J.W., J. McLuckie (1996),† Proceeding of System Dynamics and Systems

Thinking in Defence and Government,† Preparedness and Weapon System Master

Planning, University of New South Wales, University College, Canberra.

5.†††††††† Winston

Ledet, The Du

Pont Manufacturing Game pp550 , The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook† Peter Senge et al

Currency/Doubleday 1994† (email wpledet@aol.com)

6.†††††††† Bette

Gardner, Breakthrough Learning, Inc. (email: BTLng@AOL.com)

7.†††††††† K.E.

Ricci, E. Salas, J. A. Cannon-Bowers, Do

Computer Based Games Facilitate Knowledge Acquisition and Retention?,† Naval Air Warfare Center

Training Systems Division, Orlando, Florida, Military

Psychology, 8(4) 295-307.