The

Dynamics of Garbage Collection:

A System Dynamics Case Study on Privatization.

Tim Haslett

Department of Management

Monash University

email: Tim

Haslett@BusEco.Monash.edu.au

This paper outlines a consulting assignment with a local city council

in New Zealand. Local government in New Zealand, which represents the second

tier beneath the central government, had been moving towards a competition

based model for the provision of services that had previously been funded

through taxes collected through local government. Participants in a Systems

Thinking seminar identified the introduction of competition into a previously

publicly funded service, a garbage collection, as an appropriate problem for

analysis. The political imperative behind privatization in this council had

been a reduction in rates (local taxes) and increased cost effectiveness

through competition and user pays. The introduction of competition into the

garbage collection system was chosen for analysis as it had not delivered the desired

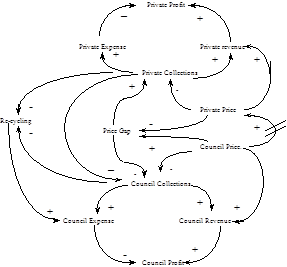

outcomes. A Causal Loop Diagram (CLD) exposed the underlying dynamics of the

situation which arose from the initial goals of the authority namely, the

introduction of the ecomonic goal of greater

efficiencies through competition and the social goal of a shift to recycling

cross-subsidized from revenue from the garbage collection.

The story that the group told for this CLD was informative. As an introduction to competition the Council

decided to begin charging a relatively low fee for garbage collection to ease

the transition from what had traditionally been a “free” (ie

funded out of local taxes) service. It was also decided to provide a “free”

(cross-subsidised) recyclable collection to move residents towards recycling

more of their garbage. Over time the price of garbage collection would be

increased to increase the amount of recycling. Thus a fundamental dynamic of

the model was a steady increase in the price the council charged to collect

garbage. The council had assumed that the price that it set for collection

would dictate the amount of recycling. It was also assumed that any private

operator would match the council’s price. However, the competitor decided to

leave entering the market until the council had raised its price to a point

where the private operator could not only discount the council’s price, but

also make a profit. Many residents stayed with the council as a matter of

principle, while others opted for the less expensive private collector. Thus

the “Price Gap” drove the relative market share of both collectors as shown in

Figure 1.

Fig 1: CLD of competitive garbage collection.

Two important policy implications emerge from the CLD. First, that

while not being required to provide a recycling service, the private collector

can set a price for garbage collection that dictates the total amount of

recycling. The presence of a competitor in the market produced a

counter-intuitive outcome for the council: a lowering of the rate of recycling.

Second, only the council is carrying the cost of recycling and this impacts on council expenses. The “behaviour over time”

graphs generated by an “iThink” model demonstrated

the dynamics of policies adopted by the council.

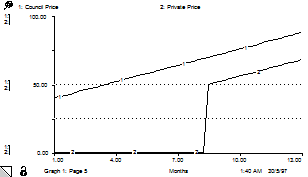

Figure 2 shows the point at which the private operator entered the

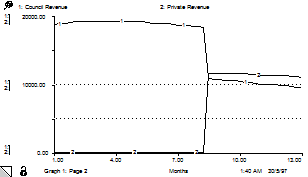

market when the collection price is 70c per unit. Figure 3 shows the impact on

revenue of the entry of the competitor: council revenue declines sharply and

the revenue of both operators declines as the price increases.

|

Fig

2: Price point for entry of competitor |

Fig

3 Relative

revenue. |

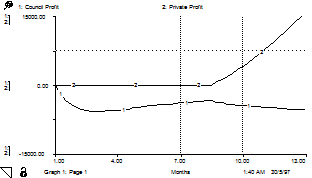

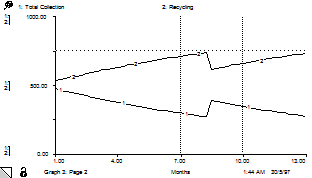

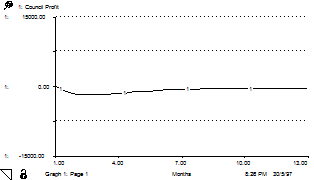

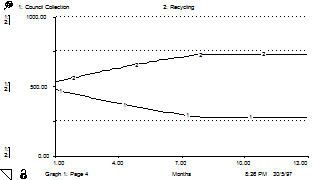

Figure 4 shows the relative profitability figures. The rising levels of recycling (shown in Figure 5), drives council

expenses up and profitability down. The competitor, who does not cross

subsidize the recycling is increasingly profitable.

|

Fig

4: Relative profitability |

Fig

5: Mix of recycling and collection |

The combination of the social policy on recycling with the economic

policy on competition set up dynamics that led to a decline in the

profitability of the council’s operation. The competitor took a significant

proportion of the council’s market share through discounting and would only

enter the market when it was profitable. In addition, the gradual shift to

recycling eroded the council’s profitability. Finally, the social policy goals

to be met through cross-subsidization, they create a disadvantage for the

council.

The simulation can now be used to test policy options. The first

is for the

council to keep its price at a level where it is unprofitable for a competitor

to enter (68c per unit). Figure 6 shows that the losses are greatly reduced

while Figure 7 shows that the level of recycling is similar to that in Figure 4

without the dip caused by the entry of the lower priced competitor. If the

recycling can generate a profit, the council may be able to break even or make

a slight profit overall. This option also delivers a lower price to the

resident (68c per unit) than the competitive model (88c per unit). The moral is

obvious: the council’s break even model is better for the residents than the

competitive model.

|

Fig

6: Council Profit - restricted price increase |

Fig

7: New mix of recycling and collection |

A number of other policy

options emerged: transfer a share of the cost of recycling to the by forcing it

to collect recyclable garbage; abandon the policy of free recyclable

collection, impose some charge and be prepared to wait longer to optimize

recycling; abandon the policy of privatization and continue to use local taxes

to achieve socially desirable outcomes in garbage collection. Another set of

dynamics was also discussed. The shire was predominantly suburban

but included rural properties where the costs of collection were higher. The

competitor was able to

“skim” the more lucrative suburban market, with the council left

with the obligation to maintain its service to the rural market. This cross

subsidization exacerbated the problems of declining council profitability.

While the council operation must maintain policies of recycling and servicing

unprofitable rural areas, it was unable to compete on an equal basis.

The exercise proved to be a simple but clear demonstration of the

counter-intuitive nature of policy. It was also a demonstration to the

participants that a deep understanding of the dynamics of policy decisions

cannot be made without the aid of systems thinking and system dynamics

modelling.